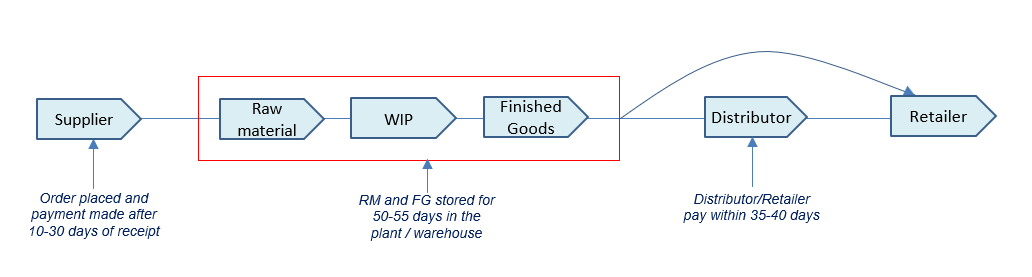

When you run a business, apart from the initial upfront capital expenditure, there is a component of capital blocked continuously into the business, called working capital. The below chart shows the flow of goods for a typical FMCG company, where capital is largely blocked during manufacturing (Inventory) and Retailing stage (Debtors):

How to calculate Working Capital (WC)?

Broadly working capital is defined as Current Assets - Current Liabilities, but more specifically, we use the following formula for operating Working Capital

A more intuitive way to compute WC is by converting the components into days, i.e. if my Debtors are 200cr for a 1200cr annual sales, on average 60 days of my sales are blocked with Debtors. This is a more practical way to look at the WC cycle, because in real life when a business extends credit sales to its vendors, it’s calculated on the basis of days (for example, Safari extend ~30 days of credit to its vendors):

Inventory days are computed by dividing Average Inventory by Annual Sales. Note, that the base can be taken as COGS, as Annual Sales are marked up with a profit amount, that is still not earned on the inventory. But we still prefer taking Sales as the base, to compare the Inventory days across different Industry:

What are the Ideal Working Capital Days?

WC helps in assessing the short-term liquidity of a business and determining how well the company can cover the payment of its forthcoming liabilities. It provides an indication of how much cash a business has tied up in current assets and whether it can cover its short-term obligations. Theoretically ideal CA:CL ratio is 2:1, but in real life, it depends on the industry the company is operating in.

Also, the company is in a constant tussle between maintaining a fine balance between Profitability and Liquidity. For example, Dmart, one of India’s largest grocery retailers, pays off its suppliers on time and can get a hefty cash discount. So in return for a higher cash discount, it has reduced its creditor days:

Now, let’s understand each item of the Cash Conversion cycle in detail:

Inventory days

It measures how many days it takes a company to turn its inventory (including goods that are work in progress, if applicable) into sales.

Low inventory days (and high inventory turnover ratio) relative to industry norms might indicate highly effective inventory management.

A high number of inventory days relative to the rest of the industry could be an indicator of slow-moving inventory, perhaps due to technological obsolescence or a change in fashion. Again, comparing the company’s sales growth with the industry can offer insight.

Receivables days

It indicates the days within which a company is collecting cash from its customers/debtors.

A high receivables days (low receivable turnover ratio) would typically raise questions about the efficiency of the company’s credit and collections procedures.

Low receivable days could indicate that the company’s credit or collection policies are too stringent, suggesting the possibility of sales being lost to competitors offering more lenient terms.

Payables days

It measures in how many days the company theoretically pays off all its creditors (like suppliers of raw materials).

A low payable day (high payables turnover ratio) could indicate that the company is not making full use of available credit facilities; alternatively, it could result from a company taking advantage of early payment discounts.

A high payable days could indicate trouble making payments on time, or alternatively, exploitation of lenient supplier terms.

Who funds the Working Capital?

Working Capital can either be funded via the company’s internal accrual or by the Channel Partners (Supplies and customers). Looking at the funding source can give you great insights into the brand pull & moat the company has.

Monopoly businesses like IndiaMart (80% mkt share in B2B e-com) & Symphony (60%+ share in Air cooler), have funded their working capital via channel partners. In some cases, they have even shown a Negative working capital cycle, clearly showing the bargaining power they command over their customers/suppliers.

For instance, IndiaMart has ~3,200cr of cash on its balance sheet, which has been due to its upfront collections from paying suppliers on the platform:

Generally, customer-facing companies & subscription-based services (Retail Chains, Multiplexes, Telecom, Music Streaming etc.) has –ve WC because customers pay upfront – so they can use the cash generated to pay off their Creditors. This can be a sign of business efficiency.

Sometimes, -ve Working Capital could point to financial trouble/bankruptcy (for example, in case the company is not paying off its creditors on time). Thus, banks while giving out loans prefer companies with +ve WC

Understanding Business Models from WC Data

Now, that we have understood the basics of WC and how to analyse it, let’s deep-dive into inferring the business model by looking just at the WC days:

Few thumb rules for analyzing working capital days:

Consumer-facing businesses (e.g. Multiplex, Retail Chains) have minimal receivable days

Services businesses (like IT and Entertainment) have minimal inventory days

WC might also vary due to business strategy. Like D-mart tries to extract maximum discounts from its suppliers by paying them up-front, they have relatively lower Payable days and better margins

B2B and Government contracts entail higher Receivable days

WC trends over time can also be analyzed to get a sense of where the company is heading.

Increase in WC: Piling Inventory, Extension of credit terms to distributors

Decrease in WC: Inability to pay thus getting relaxed payment terms; Near-term distress

Volatile WC: Change in Business Cycle; Or near-term Distress

WC remains stable: Stable businesses (FMCG, IT)

Great! Now that you have mastered the art of reading working capital, head to screener.in to look at ratios of different listed companies and try to decipher the business models using just the Cash Conversion Cycle & comparing that with its competitors